Royal penguins (Eudyptes schlegeli) are an interesting species of penguin that are best known for their distinctive bright orange-yellow feathers on the top of their heads.

In this article, we’ll uncover some fascinating facts about royal penguins, from their diet and habitat preferences to their breeding and parenting habits. Alternatively, see our main penguin facts article to learn about all types of penguin.

1. They live on small islands between New Zealand and Australia

The Royal Penguin is endemic to Macquarie Island and nearby Bishop and Clerk Islands which all sit about halfway between Australia and New Zealand. They are also found in small numbers on other sub-Antarctic islands such as South Georgia and Kerguelen Island.

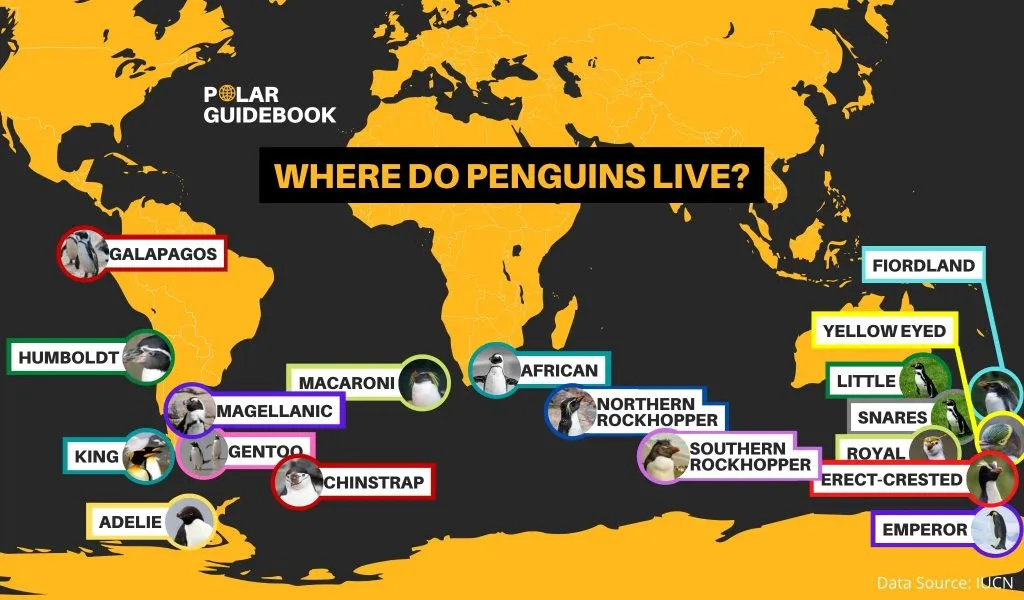

The below graphic shows where royal penguins live in comparison to the other species. See our guide to where penguins live to find out more.

2. Royal penguins are the largest of the crested penguins

Standing at 76 cm (30″) tall, Royal penguins are the =4th largest species of penguin and the largest in their family of crested penguins1 (source: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Birds: The Definitive Reference to Birds of the World, C. M. Perrins).

As for their weight, Royal Penguins typically weigh around 13.5kg (30lbs)2 (source: Australian Government) which again makes them the heaviest of the crested penguins. Only the Emperor penguin is heavier out of all the species.

3. They are easy to identify

Royal penguins are easy to spot due to their yellow/orange and black feathers in the plume on their forehead. It looks a little like they have waxed their hair backward.

Although other crested penguins have similar plumage, the royal penguin is easy to spot because it has a completely white or grey face rather than a black face like other species such as the macaroni.

4. They are black and white for camouflage

There’s actually a good reason why penguins are black and white. They are white on their ventral (belly) and black on their dorsal (back), this is called countershading and provides better camouflage for them in water.

When seen from below, their white belly blends with the lighter surface waters above, and when seen from above, their black back creates good camouflage against the darkness of deeper waters below3 (source:H.M. Rowland, The Royal Society B Biological Sciences, Issue 364, 2008).

5. Their yellow/orange feathers help them be more attractive to mates

The royal penguin has unique yellow/orange plumes on their forehead. Similar yellow feather patterns can be seen on other crested penguins too.

The yellow color is to attract a mate by demonstrating that they are healthy enough to afford to compromise their camouflage4 (source: D. T. Ksepka, American Scientist). Penguins with the most extravagant yellow feathers are the most desirable to mates5 (source: D.B. Thomas, et al., Journal of the Royal Society, Interface Vol. 10, Issue 83, 2013).

The yellow feather colors don’t come from the food in their diet like other birds, instead, it is synthesized by the penguin making it unique among birds.

6. The lifespan of a royal penguin is 15-20 years in the wild

In the wild, the lifespan of a royal penguin is between 15-20 years old which is about average for a penguin with most species living to around 20.

In captivity, penguins live a little longer, typically around 30 years although there have been documented cases of penguins living to the ripe old age of 40 in captivity.

7. Royal penguins eat fish, squid, and crustaceans

Royal penguins eat a diet of fish, squid, and crustaceans such as krill6 (source: P.D. Boersma and P.G. Borboroglu, Penguins: Natural History and Conservation, 2013).

Penguins catch and eat their food at sea. They will catch prey as they swim upwards and swallow it whole without chewing. Find out more about the diet of penguins here.

8. They lay two eggs but discard one

Our final royal penguin fact is that when breeding, royal penguins will typically lay two eggs. However, the first egg is usually much smaller than the second and is often discarded by the mother who may refuse to incubate it or push it out of the nest.

Instead, she will put all of her focus on incubating the second, larger egg. This is common among all crested penguin species.

The purpose of this strategy has been debated by scientists for many years, but the most likely reason is that the first egg is ovulated whilst the mother is still out at sea so she cannot yet fully commit herself to the egg whilst swimming for days on end. This is why the first egg is always smaller and doomed from the outset7 (source: National Geographic).

![Read more about the article Can Penguins Be Gay? [All Questions Answered]](https://polarguidebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Adelie-Penguins-1-300x200.jpg)

![Read more about the article Are Penguins Nocturnal? [Where + How They Sleep]](https://polarguidebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Sleeping-Penguins-300x176.jpg)