Penguins can live in some of the most extreme weather conditions on Earth, but they can’t throw on a sweater to keep warm. So, just how do penguins survive the cold?

Penguins are warm-blooded birds so they must keep a high body temperature to continue to function. They can survive in the cold thanks to tightly packed feathers with a down-like base and a thick layer of fat. Their feet are cold-blooded to reduce heat loss through the ice and some Antarctic species huddle together to maintain body heat.

Keep reading to find out more about the adaptations of penguins in Antarctica that help keep them warm and how they look after their young chicks and eggs.

Are Penguins Warm or Cold-Blooded?

Penguins are birds so naturally, they are warm-blooded animals (endotherms). This means they maintain a different body temperature to their surroundings.

When they are losing more heat than they are generating, warm-blooded animals must increase their metabolism to make up for the loss, this requires lots of energy which is why penguins have are great at retaining heat and can easily build up lots of energy reserves as fat.

If these fascinating birds interest you, see our full article with fun facts about penguins and prepare to have your mind blown.

Why Do Penguins Live In Antarctica?

Penguins live all across the southern hemisphere. Out of the 18 species of penguin, 5 species breed in Antarctica, these are Emperor, Adelie, Chinstrap, Gentoo, and Macaroni Penguins. Of these, only Emperor and Adelie Penguins are endemic to Antarctica as the others also breed further north.

Contrary to popular belief, penguins don’t come from Antarctica. They originate in New Zealand and Australia but have evolved into different species over time to adapt to their different environments1 (source: J. A. Vianna, et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117:36, 2020).

The first group to diverge were the Aptenodytes (also known as the great penguins) which traveled to Antarctica around 22 million years ago to make use of the abundant food resources, this group includes the modern-day Emperor and King Penguins, although King Penguins breed on sub-Antarctic islands and not in Antarctica.

The second group of penguins to diverge was the genus Pygoscelis (also known as bush-tailed penguins) which includes Adelie, Chinstrap, and Gentoo Penguins.

Interestingly, Macaroni Penguins are only a distant relative to the other Antarctic penguins as they are part of the genus Eudyptes (also known as crested penguins) which diverged much later. This is why they have a distinctive yellow crest whereas the other species on the continent do not.

How Do Penguins Survive the Cold?

One of the main methods that Antarctic penguins use to survive the cold is sharing body heat. Parents may huddle together with their newborn chicks to keep them warm or they may huddle as a large group.

Male Emperor Penguins incubate their eggs during the harsh winters in Antarctica. The birds will stay spread out during the milder days, however, when the high winds bought colder temperatures, the penguins form a large huddle.

The huddle is a large circle of penguins that gather together to reduce the amount of heat lost to the cold. They all face inwards and gradually move towards the center where those penguins that have already warmed up would make space for colder individuals.

In a huddle, there can be between 10-12 penguins per square meter and there have been observations of huddles as large as 5,000 birds2 (source: J. Younger, The Conversation, 2019) 3(source: S. Moss, Dynasties, 2018).

In the center of the huddle, temperatures can be as warm as 30°C compared to -40°C outside the huddle. This reduces the amount of energy the penguins use, they will only lose 120g (4oz) of body weight per day when huddling compared to the typical 300g (10.2oz) per day4 (source: S. Moss, Dynasties, 2018).

What Adaptations Do Penguins Have to Survive the Cold?

Here is a rundown of the main adaptations of Antarctic penguins that help them survive the cold temperatures:

1. Tightly packed feathers with downy inner parts

Whilst most birds that fly have lightweight feathers, penguins have small tightly packed feathers that lie close to their body where they keep them warm, oftentimes numbering as many as 11 per cm2 (70 per square inch)5 (source: C. Arnold, Penguins, 2013). The inner part of the feather is dry and downy to trap in warm air whereas the outer part is waterproof to protect the inner part6 (source: BBC).

Like all birds, penguins must regularly replace their feathers which they typically do once per year (twice for Galapagos Penguins), this is known as molting.

However, molting requires a lot of energy and means they cannot forage for three weeks whilst growing the new feathers. This is why they will eat excessively beforehand, almost doubling their body weight. The excess fat will keep them warm whilst they are without feathers and provides energy for their fasting7 (source: P.D. Boersma and P.G. Borboroglu, Penguins: Natural History and Conservation, 2013).

2. Thick layer of fat

Penguins that live in colder climates such as Antarctica are generally the larger penguin species compared to those that live in warmer climates such as Australia and New Zealand.

This is because they have a thick layer of fat that acts as both insulation from the cold and energy reserves for fasting when they are incubating their young and during their molt (more on this below).

The amount of fat that a penguin has will vary between species, for example, Emperor Penguins can have up to 30% of their body weight as fat whereas this is 18% among the closely related King Penguin8 (source: J.P. Robin and R. Groscolas, The Physiologist 26:A30, 1983).

Penguins need to ensure they build up the perfect amount of body fat for their time on land, not enough would result in freezing or starvation, but building up too much fat would make it more difficult for them to move around.

Penguins can add about 1% to their body fat in a single day of foraging at sea, for example, a 12kg King Penguin can grow their fat reserves by 100-120g each day, this is 2-3 times faster than the rate they lose fat during fasting9 (source: J.P. Robin, et al., The Physiologist 26:A3, 1983).

3. Low surface area compared to their body mass

You’ll notice that the penguins that inhabit Antarctica (such as Adelie and Emperor Penguins) are much larger than the birds in warmer climates (such as the Little Penguin and Galapagos Penguin), this is another defense against the cold.

Larger animals have a lower surface area-to-weight ratio, this means that the proportion of their body that is in direct contact with the cold weather is lower than a smaller animal that’s the same shape. This is why many animals found in the polar regions are large, such as polar bears, walruses, seals, and penguins.

See our full article for a breakdown of the size and weight of penguins by species.

4. Cold blooded feet and flippers via heat exchange

Although penguins are warm-blooded animals, their feet are cold-blooded, this reduces heat loss to the cold icy surface whilst on land. They do this via a heat exchange (a process called rete tibiotarsale) where the warm blood running to their toes transfers heat to the cold blood running back up to their body, this means that the heat stays within their body and does not go near the cold surface10 (source: S. Kazas, et al., Journal of Thermal Biology, Vol 67, 2017).

Penguins can control the extent of this process by changing the diameter of the blood vessels running to their feet. When they are cold, they make the vessels smaller, so more heat is kept in their bodies, when they are warm, the vessels become wider to release more warmth through their feet and cool down11 (source: Penguins International).

A study has suggested that this heat exchange reduces the amount of energy they use by as much as 25-65% compared to a typical human-like configuration.

The main muscles that control penguin feet and toe muscles are located higher up in the warmer part of their body which is essential to function. A similar process that has been recorded occurs in their flippers and even parts of the penguin face to keep the warmth where it is most needed12 (source: P. Frost, et al., Journal of Zoology, Vol. 175, No. 2, 2009).

How Do Penguins Keep Their Eggs Warm?

Penguins live in many different climates in the southern hemisphere so they have different methods of keeping their eggs warm, some will keep their eggs in nests whereas others will use their body.

Penguins are monogamous with both males and females helping to raise the offspring. King and Emperor Penguins, members of the Aptenodytes group (or the great penguins), only lay a single large egg which is incubated by the males.

They keep them warm by resting them on their feet under a fold of warm abdominal skin13 (source: C. Packham, The Science of Animals, 2019). To further maintain warmth during incubation, male Emperor Penguins will also huddle as discussed earlier.

Other penguin species will share the incubation of the eggs. For example, both male and female Chinstrap Penguins will take 5-10 day shifts to keep the eggs warm in the nest whilst the other forages for food14 (source: P.D. Boersma and P.G. Borboroglu, Penguins: Natural History and Conservation, 2013).

How Do Young Penguins Keep Warm

When a baby penguin is first born, it will have fine feathers called natal down (or it will grow them within a few weeks), this is why they look different from their parents.

Baby penguins are unable to regulate their own body temperature until their feathers have thickened into juvenile feathers so they must huddle together with their parents to stay warm. However, juvenile feathers are not waterproof so they must still rely on their parents for food until they have grown their adult feathers, usually a year later.

Among some penguin species, chicks from many parents will huddle together in large groups called a creche. These are generally located near the center of the colony and protect them from predators, weather, and aggression from other adult penguins15 (source: C. Le Bohec, et al., Animal Behaviour Vol. 70, No. 3, 2005). It is preferential to be at the center of the creche as the chicks are less likely to be preyed on. There is lots of competition with weaker chicks often getting pushed to the outside.

During extreme weather, chicks will gather as a larger creche and will turn their backs to the wind and rain.

The chicks will be left in the creche to keep them safe whilst the parents forage for food. Parents will return with food for their own chicks only, it is not like a functional nursery where adults provide communal care for all of the chicks16 (source: Seaworld).

Can Penguins Freeze To Death?

Yes, although adult penguins are well insulated against the cold, Emperor and Adelie Penguin chicks can freeze to death in the colder parts of Antarctica.

According to ecologist Rudolf Thomann, the downy feathers of young chicks puts them at a higher risk than adults because they can become waterlogged when it rains which will freeze in temperatures below 0°C.

Unlike adults who have molted their juvenile feathers and grown waterproof adult feathers, young chicks rely on their parents for warmth. Whilst the chicks can easily shake the snow from their feathers, the rain gets much closer to their skin and cools when the wind picks up.

See our full article to find out more about penguin feathers, including why they are black and white.

With the increasing temperatures in Antarctica, the frequency and intensity of rainfall is expected to increase by as much as 240% by 2100 across the continent17 (source: É. Vignon, et al., Geographic Research Letters, Vol 48, Issue 8, 2021). This will have drastic consequences for penguin chicks.

In 2017, BBC’s Planet Earth captured footage of a small group of penguin chicks that were lost in a blizzard without their parents which would almost inevitably result in death. Watch the clip here:

Related Questions

Do Penguins Have To Live in the Cold?

No, penguins do not have to live in the cold, several species have adapted to live in warmer climates such as those in South America, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Do Penguins Eyes Freeze?

Penguins that live in Antarctica can face temperatures as low as -60°C (-76°F) which would cause water, including tears, to freeze.

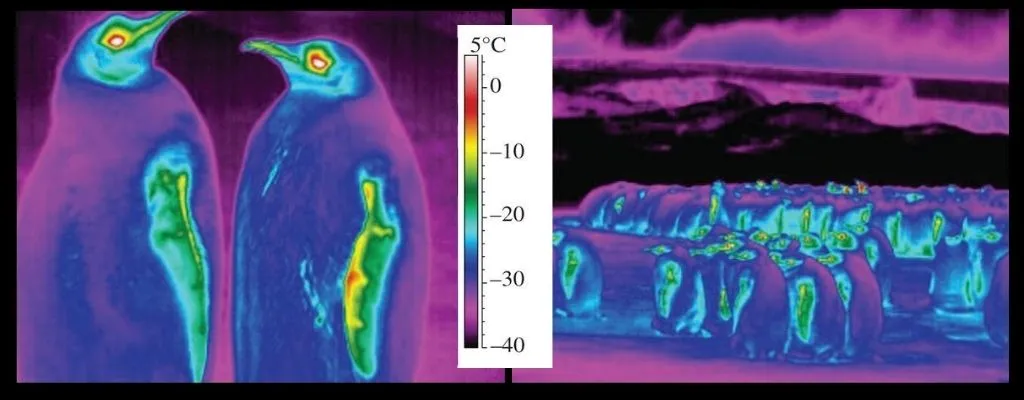

Penguins’ eyes don’t freeze because they have blood vessels that deliver warmth to the tissue surrounding them. This is why the eye region is the only exterior surface of a penguin that is above freezing, as measured by an infrared camera18 (source: D. J. McCafferty, Biology Letters, Vol. 9, Issue 3, 2013).

Do Penguins Feet Freeze?

No, penguins’ feet do not freeze because they can regulate the temperature to keep them just above freezing. Their feet are colder than the rest of their body to minimize heat loss to the cold surface but are warm enough that they don’t freeze.

To further reduce heat loss in their feet, penguins will often stand on their heels rather than their entire feet. This reduces the surface area that has contact with the cold surface19 (source: K. Rogers, Britannica, 2011). To ensure they can balance correctly, they will use their tails to balance which have stiff feathers and no blood running through them.

![Read more about the article 15 Amazing Facts About African Penguins [#9 Might Make You Squirm]](https://polarguidebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/African-Penguin-1-300x200.jpg)

![Read more about the article Why Are Penguins Black and White? [Full Color Palette Explained]](https://polarguidebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/What-color-are-penguins-300x176.jpg)

![Read more about the article 12 Fascinating Facts About Fiordland Penguins [#4 is Hard to Believe]](https://polarguidebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Fiordland-Penguin-2-300x200.jpg)